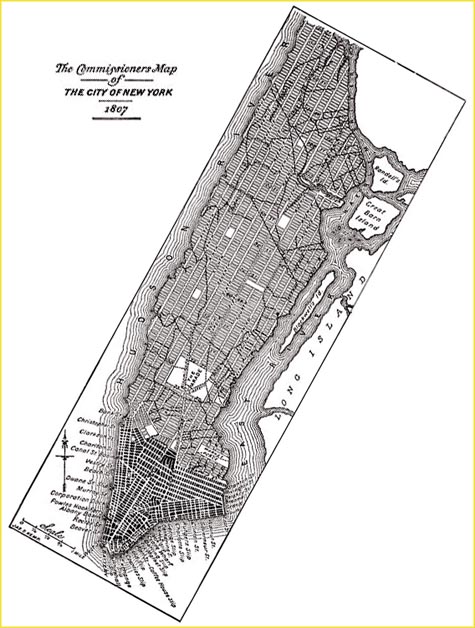

This year marks the 200-year anniversary of the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811; the plan that gave way to Manhattan’s grid system that still exists today. In fact, it’s just about impossible to imagine Manhattan without it. The often near-perfect 90-degree angles that make up the city blocks (except for pesky Broadway and a few other troublemakers) can provide people with a feeling of order in a place that is often, for residents and visitors alike, overwhelming.

Created as an orderly way to develop the city’s infrastructure, the plan was, at the time of its creation, criticized for being too rigid. However presently, the plan is most often praised for its foresight and utility. Manhattan is one of the few major cities in the world that is not bisected by a major highway, preserving a healthy pedestrian culture; something that might not have been feasible without the grid system and its wide avenues.

However many would find other faults with the plan and its creators knew it. They said so in the plan itself:

“It may to many be a matter of surprise that so few vacant spaces have been left, and those so small, for the benefit of fresh air and consequent preservation of health. Certainly if the City of New York was destined to stand on the side of small streams such as the Seine or the Thames, a great number of ample places might be needful. But those large arms of the sea which embrace Manhattan island render its situation in regard to health and pleasure as well to the convenience of commerce, peculiarly felicitous.”

The assumption was that Manhattan’s waterfront would provide an open, clean space for its citizens. Obviously, this did not work out as originally planned.

Crowded, dirty and loud, the city continued to grow without a “place” to disconnect from the realities of the rapidly changing urban lifestyle. Facing a serious civil disaster, the city didn’t begin planning a solution – Central Park – until 1850, and Central Park as we know it today didn’t really open until 1873.

The point of all of this, as it relates to enterprise social networks is that it is entirely possible to create something that perfectly solves the problem it was designed to fix which ignores other issues that can be just as dire. The health issues, both physical and psychological, that began to accumulate before the creation of Central Park would have almost certainly reached some kind of critical mass if a solution had not been found, and New York City would probably not be anything like what it is today.

It has been apparent for some time now that the way we work is changing, and much of the infrastructure needed to do that work is virtual. At least one study has already shown that some people are experiencing fatigue with Facebook, which for many people is used as a leisure activity. Who is to say that employees won’t experience a similar type of fatigue when working in a virtual environment?

As companies build there own “Commissioner’s Plan” for organizing virtual enterprise spaces, it might not be a bad idea to consider developing areas within their intranet that facilitate interaction that isn’t totally work related, at least not in the strictest sense.

Synaptics, a leading developer of human interface solutions, has built a Human Resource intranet using Clearvale Enterprise. Earlier this year, they discussed plans to creatively develop communities within the intranet for some often overlooked uses. One such community would be the platform for an “employee wellness program”, where coworkers can share experiences with maintaining a healthy lifestyle and dealing with illnesses. Synaptics hopes that this will encourage employees to interact with and learn more about one another, as well as potentially decreasing sick days and mitigating healthcare costs. Additionally, the company is considering developing an internal social network where employees can further get acquainted and get a better sense of one another’s roles within the company.

Enterprise Social Networking certainly provides us with unique way to improve workflow, but it also provides us with ways to creatively solve issues whose “2.0” version (such as fatigue) have not yet fully manifested.